Don’t let the poorly chosen title deceive you; this not a political film. Well, maybe it is. But it is not the politics from House of Cards; instead, it’s politics of Hollywood.

Robin Wright plays herself in this sci-fi animation written and directed by Ari Folman. The story is based on Stanisław Lem’s novel “The Futurological Congress.” The film circles around the “AIs will replace us!” anxiety mixed with the seemingly inevitable corporatization of people. Such darkness is expressed in a colorful animated world like the work of “a genius designer on an acid trip.”

The film opens as a few teardrops fall from the actress’s melancholic eyes. The root of her anxiety is being nothing. She is kept reminded that not being a celebrity is equal to being nothing, and she repeatedly tells nobody sees her and that she is invisible. With the desire to keep on being somebody, she takes an offer by the villainous major Hollywood studio, Miramount.

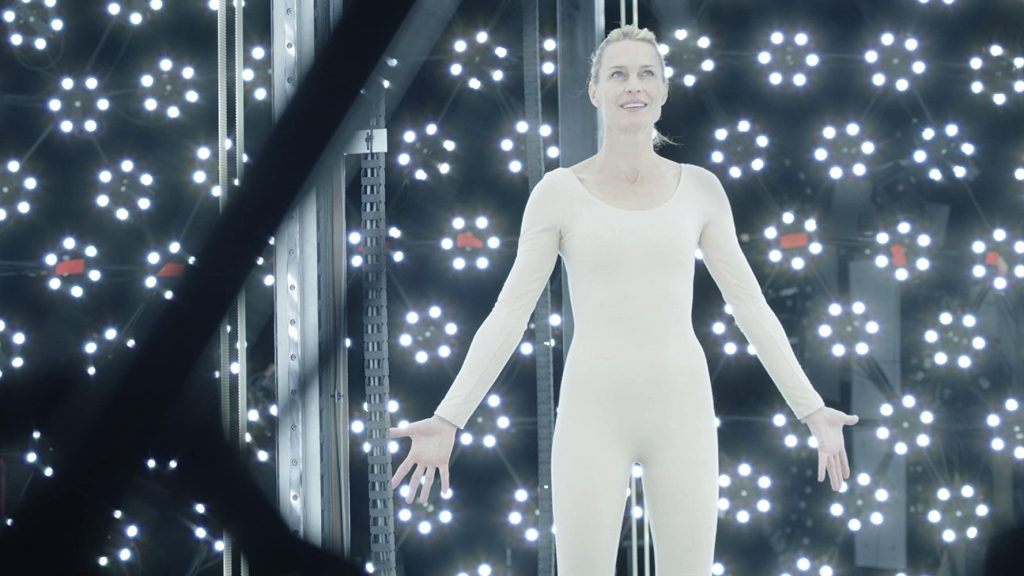

What she is offered is to create a digital replica of the actress and keep her young and beautiful, forever. Initially, it means she will get paid for the rest of her life without doing any acting. However, the deal ends up meaning not only her appearance and career is owned by Miramount, but her whole personality is open for public consumption.

The second half of the film takes place in “a restricted animation zone.” Thanks to Miramount’s high-tech science labs, people can snort whomever they want to look like. Venus from Botticelli’s paintings, Zeus, Disney princesses, Michael Jackson, Cher, and many others are among Robin Wright’s lookalikes in the Congress. The old-style cartoons and bright colors are a delight to watch, and it allows a spectacular love scene where sensations are depicted in beautiful shapes and colors.

The villain of the story has two big issues with Robin Wright: her age and her appearance. The Hollywood studio frequently attacks her as an aging actress who is just too old for the good stuff. Ironically, we see the actress with makeup to make her look older. While one points out her car looks fine for its age, she is constantly reminded that her beauty is fading away. Her agent says, “You were so beautiful,” before the studio executive goes, “You look fantastic! Animated, I mean.”

See the irony that a similar deal is done to Robin Wright for this film. For half of it, she wasn’t needed to make the film; her animated self was enough. There are many scenes where we don’t even hear her voice. The director must be fond of ironies, considering that her final performance for the studio to capture her digital replica was not even an act. They were all real feelings, her laughter fading to blankness.

“Everything is in our mind. If you see the dark, then you chose the dark.”

The film is filled with criticism and anxiety towards what the world has become or is leaning toward. The so-called death of cinema, manipulating people under promises of “free choice,” criticism against antidepressants… The Congress is dense both sub-textually and visually. It is pessimistic when it calls to look at “this side of the truth,” but also opportunistic when it hints at Hollywood’s capacity to reinvent the truth.