“Nothing but a breath–a comma–separates life from life everlasting. It is very simple really. With the original punctuation restored, death is no longer something to act out on the stage, with exclamation points. It is a comma, a pause.”

Wit is Mike Nichols’ adaptation of Margaret Edson’s same titled play which won the Pulitzer Prize in 1999. Emma Thompson ably portrays a tough scholar’s confrontation with death.

Vivian Bearing (Emma Thompson) is a professor of literature whose speciality is the metaphysical poetry of John Donne’s Holy Sonnets. Her sharp intellect on poetic death proves to have little value in the face of actual death, when she is diagnosed with stage-four metastatic ovarian cancer. Ms. Bearing believes she is courageous enough to “bear” anything, including death, however her phlegmatic nature is challenged when she accepts to undergo Dr. Kelekian’s (Christopher Lloyd) eight high-dose experimental chemotherapy treatments for eight months.

The plot circles around the paradox that she is not suffering of cancer but because of its treatment. Where every living thing is a life hazard to her, pain proves she is still alive. Towards the end, it comes to a point that letting her die is more humane than getting her heart to beat again.

Where the film is rich in symbolic attacks of the masculine towards the feminine, it is a significant symbol that Vivian has ovarian cancer. At the pelvic examination, the doctors abruptly open and discourteously touch her abdomen which makes her feel attacked, and admits that the examination was “downgrading”.

In contrast to all male doctors, there is a female nurse, Susie, whose character stands for affection, human interaction and kindness. She seems to be the only one to care about Vivian’s wellbeing. In the scene regarding the painkillers, remember that Susie wants to leave the decision of dosage to Vivian, contrary to the doctors who wish to follow the treatment regardless of Vivian’s mental condition. Jason not only restrains from making a comment, but also reflects pity.

On deciding whether they should bring her back to life in case her heart stops, Susie puts forward the fact that life is more than a beating heart. Vivian agrees that how she lives matters more than basic survival, hence declares DNR: do not resuscitate. At the scene where her heart stops, Susie’s humane insistence of letting her die conflicts with Jason’s desire to resuscitate. In S.A. Larson’s words: “With a final emphasis on the disconnection between medical provider and patient, the viewer realizes that the resident’s resuscitation attempts are motivated by the desire to prolong his research rather than by any emotional connection to Professor Bearing.”

Dr. Kelekian’s clinical fellow Jason is an old student of Prof. Bearing. How she used to be as an uncompromising professor is reflected in Jason’s character, with his ambition and admiration towards science. He is amazed by the “perfect” nature of cancer and tells it has been the only thing he has ever wanted. Where intellect clashes basic human decency, she confronts her old personality and seeks intimacy and compassion: “Now it’s time for kindness.”

There is a detail in her flashbacks. While reminiscing certain moments of her childhood with her father or her studentship with her mentor, she pictures herself as if she looked the exact way she looks now at the hospital; however while reminiscing how she acted as an uncompromising professor, she pictures her old self.

According to the interview conducted with the play’s writer Edson, “‘We understand as much as our previous experience prepares us for.’ Rather than admitting that she is feeling vulnerable, or does not understand what is happening in the hospital environment, Professor Bearing uses flashbacks to cope with the unfamiliar and regain her power by situating the unknowable present in the knowable past.”

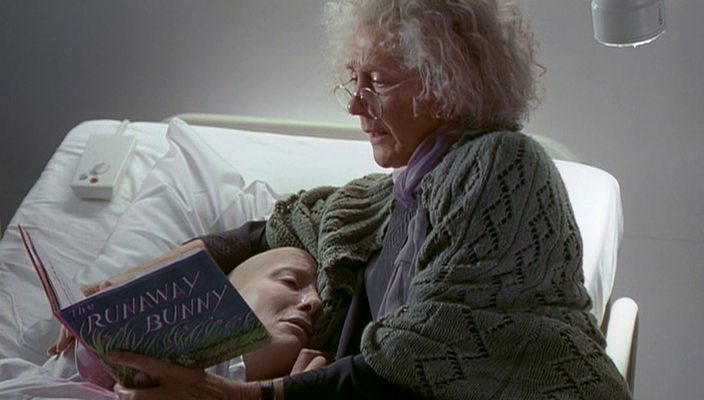

“You must begin with a text, Miss Bearing, not with a feeling.” Her old professor and mentor, whom we figure has planted the seeds of a tough Prof. Bearing, coincidentally finds Vivian in the hospital. She reads the story of “The Runaway Bunny,” which is interpreted as the allegory of soul. In Melinda Johnson’s words: “The little bunny who keeps trying to shape-shift, to become some other animal, to have some other life, mirrors the human journey to discover and improve our actual self, the one we hope to keep. And the kindly, humorous, unfailing persistence of the mother bunny is the Love that birthed us and leads us home.”

The film is very touching, yet aims to leave the viewer with a rather positive sense when considered that Vivian’s final conscious moment on screen is her laughing with Susie, and the final image of the film is a photograph of her before the treatment began.

Technically speaking, the film has visibly adopted certain features of the play that it is based on. The fact that the main character speaks directly to the camera to express her deepest truest feelings leads to complete internalization of the whole treatment process. Thus the film is rich in close up shots, as well.

Breaking of the fourth wall to express directly what is going on inside the character’s mind naturally leaves little for the viewer’s interpretation; which in this case, we might conclude that the filmmaker had direct intentions of promoting a humane connection between a doctor and their patient. In this sense, Wit is one of the suggested films for all medical students and doctors.